“Excellent article on the conquest of Canaan by Joshua and errors made in it’s dating.” Admin

When Palestine was first opened to archaeologists, they were excited to seek evidence of Israel’s Conquest. When the findings didn’t match their expectations, they decided to throw out the Bible rather than question their assumptions.

At first the digs were promising. One of the first cities excavated in Israel was Jericho, the first stop in Joshua’s campaign of conquest in the Promised Land. A group of German scholars did the first excavations at Jericho in the early 1900s. In the 1930s, British archaeologist John Garstang started new excavations at Jericho, finding local Canaanite pottery from Joshua’s time and evidence for massive destruction by a fierce fire, including ash deposits up to 3 feet (1 m) thick. The evidence was consistent with an Israelite attack on the city around 1400 BC, the biblical date for the Conquest.1

Then in the 1950s, Garstang’s colleague Kathleen Kenyon continued excavations at Jericho, but she reached a much different conclusion: Jericho was not destroyed at the time of Joshua but 150 years earlier, around 1550 BC. Indeed, she claimed the Canaanite city was unoccupied when the Israelites supposedly entered the land. Hence, there was no city for the Israelites to conquer.

Kenyon’s conclusions quickly became scholarly dogma.

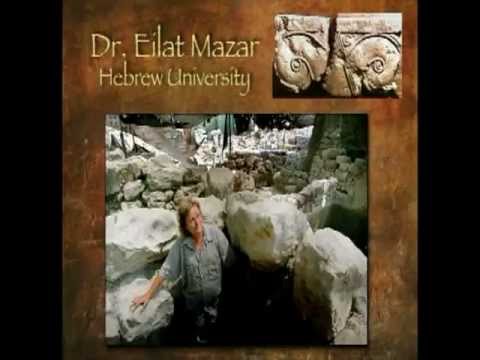

Kenyon’s conclusions quickly became scholarly dogma. Those conclusions are still held tenaciously by most archaeologists and Old Testament scholars, despite the work of a later archaeologist, Bryant G. Wood, who demonstrated Kenyon’s dating errors and lack of in-depth analysis of the pottery.2

What led to this rejection of the Bible’s timeline? Before Kenyon’s pronouncements, archaeologists had difficulty finding archaeological evidence of a large population influx and widespread destruction throughout Canaan around 1400 BC. They had expected to find lots of evidence that Israel had overthrown the old Canaanite cities and culture and established their own, unique material culture throughout the land.

Since evidence for such an influx seemed to be missing, they developed a new idea: the arrival of the Israelite people must have coincided with military clashes in Canaan during the thirteenth century BC. (This was the violent era of the Judges, though secular archeologists don’t recognize this connection.) The promoter of this idea was William F. Albright.3

In due course, archaeologists were unable to find enough archaeological evidence to finger the Israelites as thirteenth century invaders, either. As a result, a majority of archaeologists and Old Testament scholars jettisoned any notion of a historical Conquest at all and began formulating esoteric and unbiblical theories for the origin of Israel.4

So, what are serious-minded Christians to do about this “problem”?

Read more here: AIG Daily

Thanks! Share it with your friends!

Tweet

Share

Pin It

LinkedIn

Google+

Reddit

Tumblr